|

|

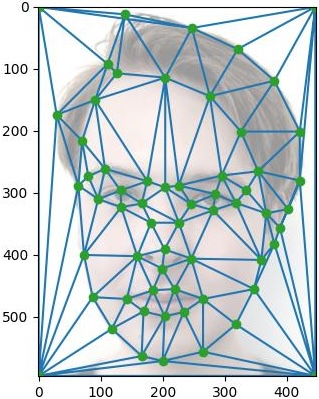

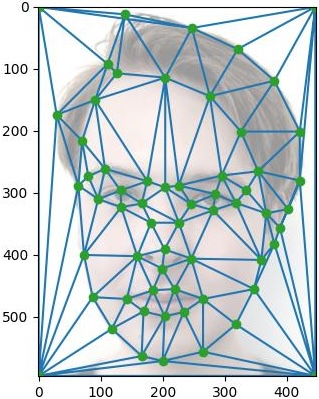

|---|---|

| Me (Max) | Brayton |

|

|

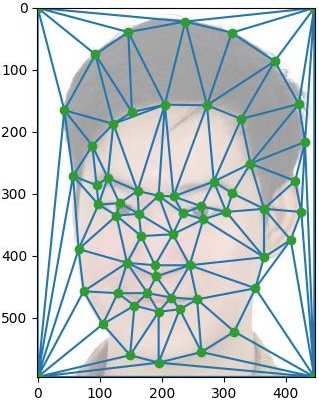

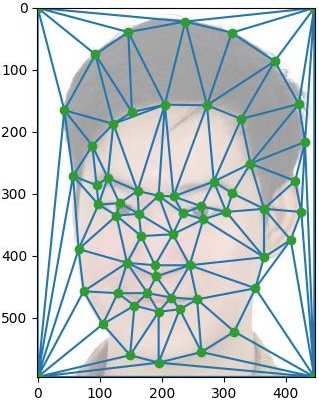

|---|---|

| Me (Max) | Brayton |

Mid-way Face

|

|

Morph Sequence: Brayton to Me

|

|---|

| Original Image | Warped Image |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average Face (Danish Dataset)

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Average Face to My Geometry | My Face to Average Face Geometry |

Morph of Average from Danish Dataset to Me

|

|---|

|

|

|---|---|

| Average Face, FEI, Neutral | Average Face, FEI, Smiling |

|

|

| Average Face to My Geometry | My Face to Average Face Geometry |

Morph of Average from FEI Dataset to Me

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| Danish Dataset, Alpha = -0.5 | Danish Dataset, Alpha = 1.5 |

|

|

| FEI Dataset (Neutral), Alpha = -0.5 | FEI Dataset (Neutral), Alpha = 1.5 |

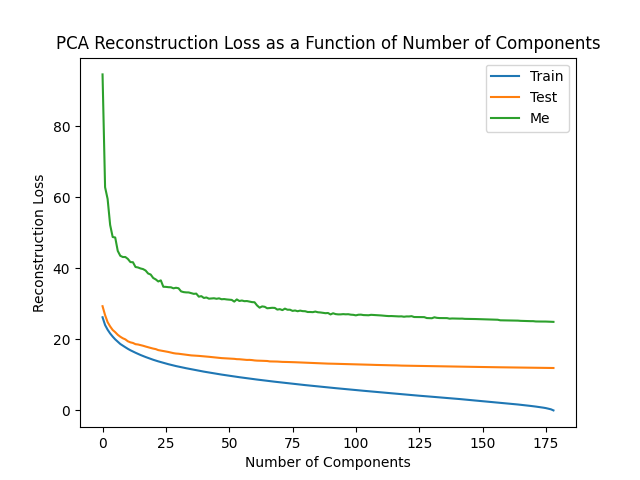

| Average of Train Images to Me | Average of Test Images to Random Test Image | Average of Train Images to Random Train Image |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

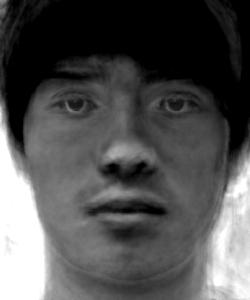

| Me From Train Average | Test Example from Test Average | Train Example From Train Average | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Image |  |

|

|

| Target Image PCA Reconstruction |

|

|

|

| Alpha = 1.5 |  |

|

|

| Alpha = 2 |  |

|

|

| Alpha = 3 |  |

|

|